UPDATE, JUNE 2019: For more detailed and updated information on the production totals of the Speedmaster 125 please visit my site speedmaster125.com. My projections turned out to be correct!

I recommend reading about the backstory on my serial number project and how I estimate production numbers based on serial numbers.

Before I throw more math at you, let me briefly recap the generally accepted story of the Speedmaster 125.

The Speedmaster 125 was initially released in 1973 to celebrate the 125th anniversary (quasquicentennial if you’re a fan of long words) of Louis Brandt’s founding of his watch shop at La Chaux-de-Fonds. It was an expensive piece at the time. In a US catalog from 1973 reproduced on old-omegas.com, the Speedmaster 125 sold for $425 while the moon watch ref. 145.022 was $225. The watch was heavily promoted, appearing in period catalogs from 1973 through 1975, but the high price and the huge, heavy, and non-traditional case may have contributed to slow sales. Extracts from the Archives show that the 125 was still being made as late as 1976 and an example from the 2007 Omegamania auction had sales documentation of an example being sold in 1977. The serial numbers I’ve collected show that a big chunk of the highest serial numbers (in the 38 million range) of any watches in the cal. 1040/1041 family were Speedmaster 125s, suggesting the Speedmaster 125 didn’t do well in the first wave (35 million range).

Forty-three years after its introduction, they are still common on the market, even more so than several cal. 1040 contemporary references. They are also more commonly seen for sale than other more recent Omega Limited Editions that were made in similar numbers (think Japan Racing LE 3570.40 of 2,004 pieces from 2004 and the Planet Ocean cal. 2500 Liquidmetal LE of 1,948 pieces from 2009).

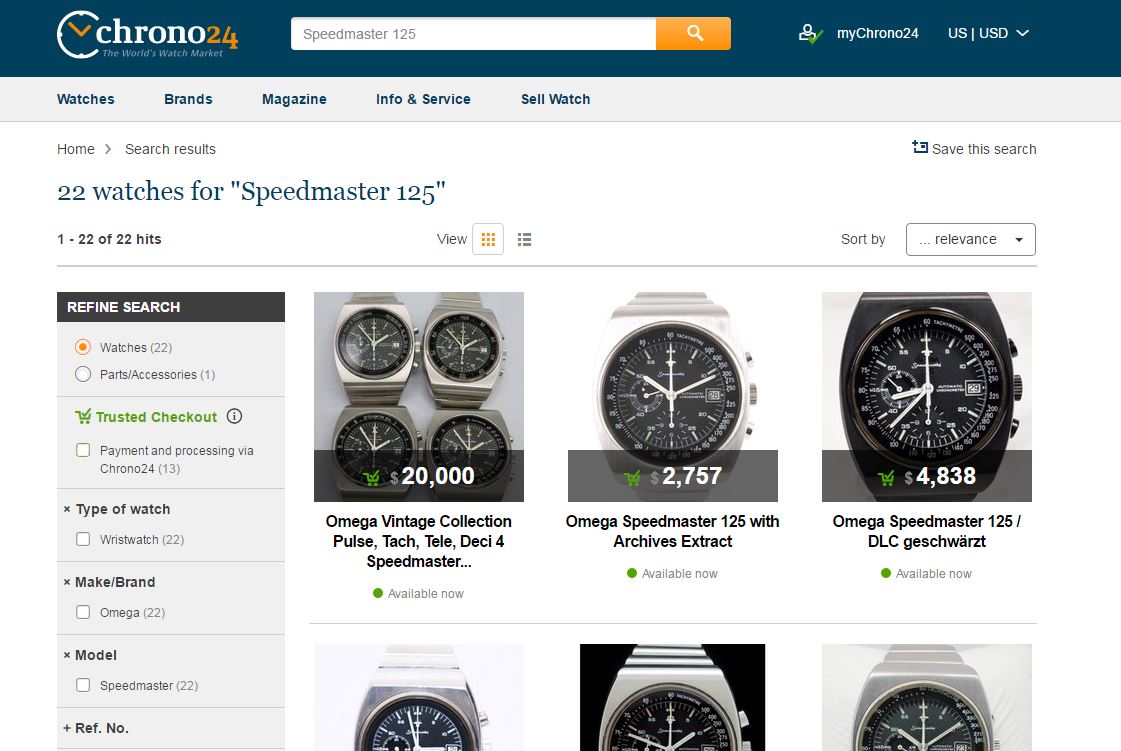

Here’s a search performed in September 2016:

This is surprising given Omega often cites that this watch was limited to 2,000 pieces and it seems they have been more common than expected for many years. Chuck Maddox pointed this phenomenon out in an article he wrote in 2000. The general consensus has been that collectors rarely hang on to this watch and tend to flip it because of the extreme size and weight. This, the theory goes, would explain the high numbers of examples for sale. In other words, simple high turnover of the same examples we see on the market. There have also been replacement dials, cases, and bracelets available on the market for years, which leads to the possibility of ordinary 1040 movements being recased into “NOS” 125 builds, similar to the “Watchco” Seamaster 300s.

The watch itself isn’t marked as a limited edition with a number XXXX/2,000. Some were stamped with an alphanumeric code on the back, but others weren’t. It is unclear what that code signified, if anything. And oddly, the early promotional materials and ads don’t mention the 2,000 figure but referred to it as “commemorative”; Omega only started referencing that number later. Because of the surprising availability, lack of markings, and lack of early references to 2,000 pieces, several people have wondered aloud whether Omega might have actually made more than 2,000 examples. If this theory is true – that there were more than 2,000 made, then the dates of sale and manufacture I just described lead to a completely opposite interpretation (and the phrases above in bold that many people have accepted as fact over the years are actually false assumptions). Maybe the 125 sold so well, and at a high mark up, that Omega just kept making them. The Swiss watch crisis was just starting to hit in 1975, so its possible that Omega wanted to move as many popular, high-margin pieces as possible.

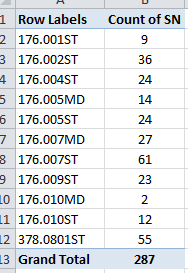

Back to the math. From November 2015 to April 2016, I observed 55 Speedmaster 125s. If the 2,000 figure is correct, then I’ve seen 2.75% of all cal. 1041s produced. That seems like a high percentage of serial numbers to be observed in a short period of time to me. So what is a more realistic percentage that I should have expected to have seen? If only there was a similar movement, with a similar collector following, from the same era, that we had some observed data on, with a known production figure….Oh yeah! Cal. 1040.

Recall that I’ve observed 232 of all 82,200 cal. 1040 serials in the exact same timeframe using the same methods. That works out to 0.282% of all cal. 1040s observed during a 6 month window, 40+ years after being made. So why have I been able to observe 2.75% of all cal. 1041s during the same timeframe, also 40+ years after manufacture?? Comparing those percentages (1041 observed : 1040 observed) yields a ratio of 9.744 to 1. That number quantifies the phenomenon that Chuck Maddox and numerous other collectors have experienced: it seems like there are more Speedmaster 125s out there than you’d expect. And that ratio confirms that the Speedy 125 is seen nearly 10 times more than you’d expect!!

So which number do we trust? The 82,200 production number of cal. 1040 from AJTT, or the 2,000 production number of the Speedmaster 125, also from AJTT?

I’ve observed 232 of all 82,200 cal. 1040 serials produced. That works out to 0.282% of all cal. 1040s. So why have I been able to observe 2.75% of all cal. 1041s during the same timeframe?

For the moment, let’s assume that 2,000 is incorrect, and that for an Omega sports chrono of that era, a collector like me should be able to observe 0.2822% of all the pieces in the observation period of November 2015 through April 2016. Extrapolating using those assumptions gets us to a production estimate of 19,487 Speedmaster 125s! That’s a far cry from 2,000. Look closely at the extrapolated cal. 1040 production figures – Omega was likely to have produced more than 2,000 of even the infrequently seen 176.001 and 176.010. Remember, for at least 15 years, collectors have been pointing out that the Speedmaster 125 doesn’t seem uncommon enough for a piece from 1973 that was limited to 2,000 pieces. Since we have a sampling of its contemporaries with cal. 1040, we can infer how often we should expect to see it. Not only is it much more common that you would expect, but it should be even less common than any cal. 1040 except the 176.010 MD and the 176.007 BA.

Foil Hat Time -So here’s the theory: Someone at Omega just dropped a zero and Richon and others went with that number. As simple as that. The real production number was 20,000. This explanation is simple and explains the “factor of ten” discrepancy. I work with data for a living and any time results appear to be 10x off of the expected result, a red flag is raised and a hunt for an extra or dropped zero or shifted decimal point begins. In almost all instances, one of those ends up being found and the discrepancy is resolved.

Other Possible Explanations

Possibility 1: The 1041 movement is more commonly shown online than cal. 1040. Perhaps sellers feel more compelled to prove that the movement in a Speedmaster is a cal. 1041 and not a more common cal. 1040 because buyers know the movement is exclusive to the watch. Yes it seems sellers should show a movement shot but… because the serial on a 1041 can be hidden by the rotor, movement photos of cal. 1040 are actually more likely to show a serial number than movement pics of a 1041. So I don’t think this results in the factor of 10 and if anything, the SN being on the rotor of cal. 1040 but not 1041 would make the 1041 less likely to be shown online.

Possibility 2: The aforementioned propensity of collectors to “flip” Speedmaster 125s. Perhaps more people hang onto their other 1040s and more people flip Speedmaster 125s, leading to more FS ads and thus more movement pics. Maybe, but again we’re talking about a factor of 10. Are Speedmaster 125s really ten times more likely to be flipped? I doubt it.

Possibility 3: The number of serial numbers observed has no meaningful correlation to production volume. Maybe certain references’ casebacks are harder to remove to allow documenting or photographing the movement. Maybe certain models were marketed to parts of the world that are unlikely to pop up on my searches of the western internet. Maybe the Speedmaster 125 is just talked about relatively more often than its contemporaries due to its unusual looks. This is kind of a generic “other” explanation to account for this discrepancy.

Possibility 4: AJTT/Omega is wrong about the 1040 production numbers, and there were much fewer than 82,200 made. Seems unlikely to be the sole reason for the discrepancy. We’re talking about a factor of 10x, which would require the real number of cal. 1040s to be closer to 8,000 for the Speedmaster 125 numbers to make sense, and that would make the real numbers of specific references of cal. 1040 to be REALLY small.

Possibility 5: AJTT/Omega is wrong about the 1041 production numbers, and there were much more than 2,000 Speedmaster 125s made. I’m a believer.

I welcome any other theories or insights. I don’t think I’ve proven anything but I do think that these results are rather compelling, enough so to cast legitimate doubt on Omega’s official story of 2,000 Speedmaster 125s.

Further Reading: Unanswered questions surrounding the Speedmaster 125, including the mysterious alphanumeric caseback code and the true production totals.

Additional information about Speedmaster 125 Caseback Codes suggesting more than 2,000 produced.

NOTE: This is an edited version of the original posts I made on Omega Forums in April 2016. Check out my Current Production Estimates page to see how the numbers have fluctuated over time.