The cal. 1040 family is possibly the loudest and boldest group of watches in terms of style in Omega’s history, typified by large, chunky cases and colorful and asymmetrical dials, bezels, and hands. Strange then that Omega opted to launch this new movement, their first ever self-winding chronograph, in the comparatively austere 176.001, a humble cushion case that lacks a timing bezel.

Available only in steel, the 001 was a Seamaster. Again, this is a strange choice for Omega if they were hoping to launch a new top-of-the-line chronograph movement. You’d think they’d ride the recently earned “First Watch on the Moon” credibility and immediately roll out the 1040 on a Mark III Speedmaster before a plain old not-quite-dressy, not-quite-sporty Seamaster chronograph. Then again, maybe they didn’t want to cannibalize sales of the Speedmaster Pro right away by offering a Speedy housing a “new and improved” automatic movement. Or maybe they actually released both at approximately the same time? We’ll come back to that question in a bit.

176.001 is perhaps best known for being the shortest-lived, least common and least understood reference of the cal. 1040 family. It is certainly the least documented – it is the only 1040 reference not pictured in A Journey Through Time, and it never appeared in the period ads or catalogs. Curious for a watch that represents a huge technological step forward for Omega.

Similarity to 176.007

Novice collectors could easily mistake the 176.001 as a 176.007 with the bezel missing. The cases are very similar in size and proportion, and the casebacks are interchangeable. The case is subtly different on the top area surrounding the crystal. A 176.007 case features one continuous surface from the crystal to the case edges which features a sunburst finish radiating outward. The 176.001 case features a small ring of flat surface immediately around the crystal, before the main sunburst top surface starts. This gives the appearance of a fixed plain-steel bezel. Close inspection reveals that the timing bezel (usually a tachymetre) of the 176.007 is on the inside of the crystal, occupying the real estate that the flat plain steel “bezel” occupies on a 176.001. This results in the 176.001 requiring a smaller crystal than the 176.007 and giving the illusion of being a smaller watch since the dial appears smaller, plainer, and less sporty without a tachymetre ring.

The casebacks are a source of confusion as well. All 176.001 casebacks should be marked as such on the inside, but many early 176.007s are marked “176.001 176.007″. I’ve even seen some 176.007s with 176.001 only on the inside of the back. This leads to some people misinterpreting the stampings to mean that the watches are the same and Omega just updated the case reference at some point from -001 to -007. The accepted explanation however is that the 176.001 was discontinued abruptly while Omega still had cases in stock. The cases were altered to accept a larger crystal and internal bezel while the caseback stock was renamed ref. 176.007.

The final similarity between these references is the dials. All of the dials seen on the 176.001 are also common on the 176.007.

The issue of primacy – Let’s examine the evidence

Assigning dates to the 1040 family and specific references within is tricky, and determining primacy – which watch, dial, handset, etc. was released when- is very difficult. There are various sources but even the most authoritative (AJTT, the Omega Museum, the Omega Vintage Database) contain contradicting evidence. Dating an Omega by serial number is at best only a rough estimate. Extract of the Archives data is probably the most instructive, but I haven’t found enough photos online of cal. 1040 EoA to draw any new conclusions, and none of a 176.001. [EDIT September 2017: I now have seen an extract for this reference. Read more here.] As such, collectors over the years have formed certain rules of thumb based on assumptions and conclusions drawn from the spotty source material.

Exhibit A: A Journey Through Time

Two key sources point to 176.001 being Omega’s first self-winding chronograph reference, the first being Marco Richon’s A Journey Through Time. Ref. 176.001 is never pictured in A Journey Through Time, but it is mentioned in two captions. The caption next to a museum example of ref. 176.007 dating to 1971 ends with the parenthetical “ref. ST 176.0001, which became the ref. 176.0007 ST in 1972”. This caption is unfortunately worded, because the watch pictured has a tachymetre bezel, and is clearly a 007 and not 001. Although purely conjecture, my guess is that this is an early example of 176.007 with the caseback showing a crossed out 176.001 on the inside. The phrase “which became the ref. 176.0007” certainly suggests that 001 preceded 007, but the incorrect identification of the case muddies the waters a bit. There’s a chance that Omega’s records weren’t especially clear and the author just wasn’t too familiar with this particular family of watches, or it was just a poor translation in the text. If that’s the case, it’s hard to draw conclusions from this caption alone.

[UPDATE – November 21, 2016: Click here to read more about the inconsistencies A Journey Through Time pertaining to cal. 1040]

Exhibit B: The technical guide

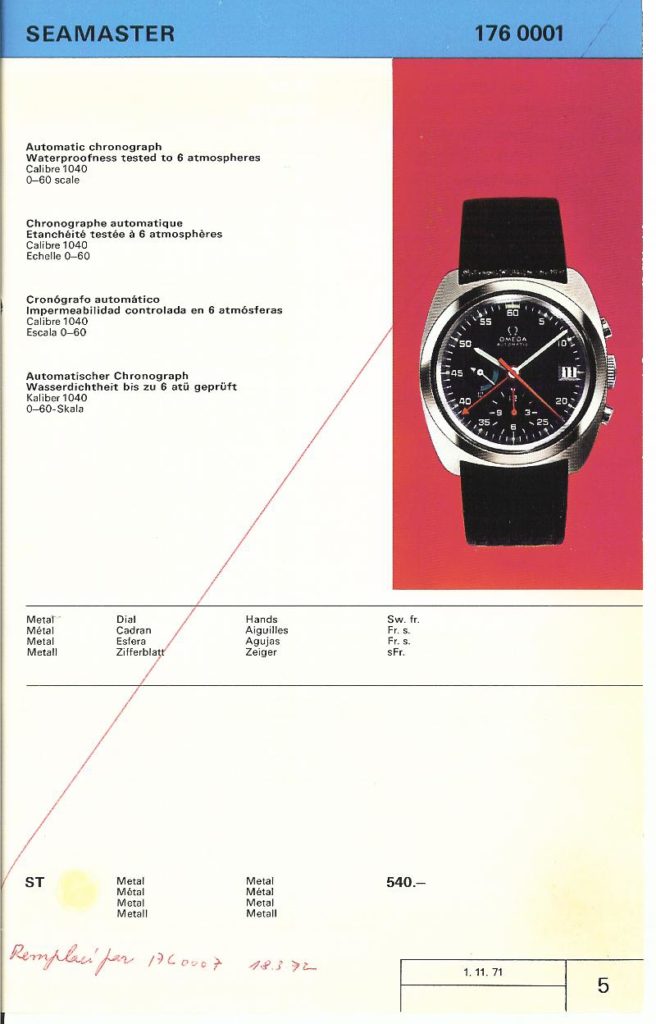

The second, and most compelling piece of evidence comes from an early technical guide published by Omega and provided to watchmakers as a parts and service guide. There are three such technical guides that I’ve run across and the earliest one is interesting for a few reasons. The cover of this guide shows ref. 176.001 sporting a very unusual dial and handset that never found its way into production. The guide is dated November 1, 1971, and was posted to Chronocentric in 2007 by Steve Waddington (owner of www.old-omegas.com), who believed it was sent to him by one of his contacts at the Omega Museum.

The interesting part is the handwritten note on the bottom of the document, which when translated from French says “replaced by 176.0007 18.3.72”. Who wrote that note? A watchmaker, or someone from the Omega Museum? That’s not known, but it clearly implies that reference 176.001 preceded 176.007. Interestingly enough, there is a 1972 version of the technical guide that depicts 176.007 MD, and a modern (includes Swatch Group logo) PDF version of the technical guide depicting the same 176.007 MD, that dates the movement (incorrectly) to 1972.

Exhibit C: Styling cues

Certain design features suggest the 176.001 was an early watch in the series as well. The minute hand seen on most 176.001s is the “needle tip” or “syringe” type hand, which is commonly believed to be the earlier variant for 1040 references. Also, the blue-dialed 001s almost always display the less common “OMEGA Seamaster AUTOMATIC” or “OSA” text order. It seems as if the later Seamasters in the 1040 series tended to favor the “OAS” text order. Wedge and Flag dials all use OAS.

Exhibit D: The Omega Vintage Database

The Omega online vintage database adds to the case of 001 being the first, too. When you search any of the cal. 1040 references, the database gives the year production began. 176.001 and 176.002 are the earliest, giving 1971 for the year while 004, 005, and 007 debuted (per the database) in 1972.

Exhibit E: Serial numbers

Serial numbers also support this claim. When sorting observed cal. 1040 and 1041 serial numbers numerically the majority of the low serial numbers are found in 176.001.

Exhibit F: It’s all in the name

Finally a major and quite logical reason to believe 176.001 was the first watch in the cal. 1040 family is the reference number itself being “001”. Sure sounds like the first in a series to me. Just speculation but it’s easy to imagine that 002, 004, and 005 were already in planning stages which is why the actual replacement used a higher number, 007 in this case. There is no 003 or 006; they could have been planned watches that never made it to production. There’s no proof of this explanation, but it is simple enough.

The verdict

The AJTT caption, the technical guides, the order of reference numbers, the serial numbers, the design features, the vintage database, and the existence of 007s with 001 crossed out don’t individually prove anything, but they together they do present a compelling case for being first. Unfortunately, there’s plenty of conflicting information that point to other watches being first out of the gate.

Clouding the Issue

Many point to the original technical guide and the French hand-written notes as the source of dating the 176.001 to only being produced during the small window between the date the guide was printed (November 1, 1971), and the date the hand-written notes indicate the 007 replaced the 001 (March 18, 1972). This is a period of less than 5 months, and it seems reasonable to many considering how few 001s seem to have been made compared to the 007. But I’m not sure I agree with those assumptions.

Let’s start with the date printed on the guide. This is really just the effective or printing date of a service manual, not necessarily the date production began on the 001. Remember, this is a document the covers all watches of all references that house calibre 1040. It is the earliest known such technical guide for cal. 1040, but there may have been an earlier version. So production of ref. 176.001 could have began earlier (remember, Omega commonly cites cal. 1040 as dating to 1970). It may just be that Omega didn’t get around to printing the official service guide for this calibre until November 1971.

Then there’s the handwritten notes suggesting that 176.007 replaced 176.001 on March 18, 1972. The conclusion that seems to have been drawn from this evidence is that as of that date Omega stopped assembling 001s and started assembling 007s. That might only be half true, if at all.

AJTT on page 550 shows a group of three 176.007s. The purpose of this picture was to demonstrate that there were in fact bezel options other than tachymetre. However there are a few inaccuracies in the caption. Most obviously, the caption identifies these as 176.001s – an odd reference for a photo that exists to discuss bezels; a feature the 176.001 plainly lacks. Second, the caption describes all as having riveted baguette hour markers, but one obviously just has racing-style painted lume. Finally, all three are identified as being from 1971. The caption does call out that 176.001 was replaced by 176.007 in 1972.

AJTT‘s Contradictions

So the handwritten notes suggest and the Omega vintage database indicate that 176.007 debuted in 1972, but AJTT shows three 176.007s that are all dated to 1971. This contradiction leads to a few options. First, the dates of the watches could be wrong and these are watches from 1972 or later. AJTT says on page 7 that throughout the book the year in the caption is a year of production, but it doesn’t specify how that year is determined – is it from the actual archive records or is it through less reliable serial number estimation? Second, the vintage database (and caption) could be wrong as far as the year 176.007 was introduced. Maybe the 176.007 went into production in 1971 as the caption suggests, and the handwritten date is only referring to the date that 001 production stopped. That would imply multiple cal. 1040 watches being produced simultaneously.

Simultaneous release of multiple references with a new movement isn’t a difficult to imagine scenario. In fact it seems to have occurred many times in Omega’s history (One recent example would be cal. 9300 debuting in the Speedmaster, Seamaster Planet Ocean, as well as the DeVille). Again, the vintage database dates both 176.001 and 176.002 to 1971. It could be that Omega released both a Seamaster and Speedmaster to the market some time in 1971, and along the way they phased out 001 and phased in 007 as the Seamaster variant.

At one point in AJTT, ref. 176.002 is referred to as Omega’s first self-winding chronograph. Again, this could be the case simply of a poorly translated caption, and the “first” was intended to refer to the movement. Earlier in the book, it is correctly called out as the first automatic Speedmaster in a “Space” timeline, and 1971 is the year given. AJTT also famously shows a Seamaster-dialed ref. 176.002 which it describes as the “precursor” to the Speedmaster Mark III. This confuses things even more. Basically it suggests that before there was a Speedmaster version of 176.002, there was a Seamaster version. And multiple sources cite 1971 as the year the Speedmaster Mark III was launched. So if the Seamaster 176.002 was a true production model, it was released in 1971 (or even 1970?).

[UPDATE – November 21, 2016: Click here to read more about the inconsistencies A Journey Through Time pertaining to cal. 1040]

1970 – What can be gleaned from the story of other early chronographs

Let’s take a step back and examine the basis for the claim, cited several times in AJTT, that Cal. 1040 dates to 1970. On page 550, there’s a blurb about how the ball bearing system was patented by Marius Meylan-Piguet for Lemania on December 28th, 1970. The next paragraph begins “Although an early automatic chronograph, the calibre 1040 was not the first automatic chronograph calibre in the world..” and goes on to give credit to the El Primero and Chronomatic movements for being first in 1969. Seiko is not mentioned. The paragraph wraps up with mention that had Omega/Lemania could have been first because they had made non-production demo models back in 1946.

In 2008, Jeff Stein wrote a terrific article analyzing the race be first to market with an automatic chronograph. In it he describes how Zenith worked off and on since 1962 and made a pre-emptive strike when they got wind of how close the Heuer-Breitling-Buren-Hamilton Chronomatic group was to launching their movement and announced the El Primero in January of 1969. He describes that the Chronomatic group had been in the planning stages since the 1950s and had 100 working pre-production watches in late 1968, announced the watch in March 1969, and released their watches in full production by the summer of 1969. Seiko’s records weren’t as clear, but it seems their chronograph, ref. 6139, was on the market in the spring/summer of 1969 too. The El Primero finally hit the market in late 1969.

Stein’s article make no mention of the development of cal. 1040, which is based on Lemania’s cal. 1340. AJTT attempts to give Omega and Lemania credit for being close, but how close were they, really? Is Omega spinning the story to make them look as if they were closer to the leading edge, and not left behind? I ask these questions because Omega frequently uses 1970 as the release date for cal. 1040, but the event it is tied to, that patent for the ball-bearing rotor mounting system, happens to be only 3 days from 1971. This is almost a full two years after Zenith’s announcement, 21 months after the Chronomatic announcement, 18 months after the Chronomatics and Seikos hit the market, and more than a year after the El Primero hit the market.

Further, while Omega points to cal. 1040 as dating to 1970, all of the actual watches that housed cal. 1040 are dated, per Omega, to 1971 or later. We know that the Zenith and the Chronomatic Group had a lag between announcement of movement and release to the public for sale (i.e. serial production), and it appears that Omega had such a lag too. Unanswered is how long 1340/1040 were in development – was it a hurried response to the announcements from their rivals, or was this something that had been in the works for years? The quality of the finish, the ability to meet chronometer standards, and the overall finish of cal. 1040 suggest that it wasn’t rushed, but I can only speculate.

Also unclear is when the watches, 176.001, 176.002, and others, actually hit the market. Without detailed archival data we must go with the sources we have. And since the sources are so often contradictory we have to make some educated guesses. Though watches may have trickled into stores in 1971, Omega wasn’t marketing them yet. Steve Waddington’s site has several ads and catalogs from the period, and cal. 1040 doesn’t make an appearance in the catalogs until 1972 and isn’t shown in ads until 1973. AJTT shows many ads as well and the Speedmaster Mark III ref. 176.002 was the only 1040 to make an appearance in a 1972 ad. It seems possible that the reason we don’t see 176.001 in ads might be that it was discontinued before Omega was ready to ramp up production.

Conclusion

What are we to make of 176.001? Is it an important historical piece for Omega representing the last great complication? A historical oddity that Omega quickly removed from production and then made little effort to commemorate? Both? Based on the facts, assertions, and scant hard evidence that exists, I believe a convincing case can be made for the 176.001 being a truly significant reference in the history of Omega. How strange then that 176.001 is treated as more of a footnote by Omega, a brand not shy about celebrating its milestone achievements?

Main Image Source: Chronocentric, user SteveW62

Fascinating stuff. Really well-researched, thank you! My burning question, perhaps even more difficult to answer, is why 176.001 was discontinued at all. Did market research (or poor early sales) indicate that people desired a tachymeter scale? Would it be a common occurrence for models to be discontinued so quickly? Are there any precedents?

I suppose the Omega archives might hold the answers…

Thanks for the kind words! I agree, knowing why would be very interesting. It’s a beautiful watch in its own right, even without a timing bezel.

As a owner of a 176.007 I loved the read. for me a tachymeter scale on a chronograph has become such a natural ‘companion’ since …. well juts lets say I had a few of them 😉

I like the lemania/omega movement, as it is so natural ro read – especially as I get older, but even before, if not just seconds are being measured.

Great read, good research – love it!

Thanks, I have more than a few as well, and the 176.001 is the only one without a tachymetre or some kind of timing bezel. Glad you enjoyed the article!