This is the third and final post in a series designed assess the accuracy of the most authoritative and commonly cited sources for collectors when it comes to Omegas of this era. My aim is not to discredit these sources or promote my own conclusions to the detriment of their positions. Rather, I hope to further conversation and offer a differing point of view and back it up with the data and observations shared on my site. Part I covered the writing of Chuck Maddox. Part II covered A Journey Through Time, by Marco Richon.

Omega’s Vintage Watch Database

No matter how long or storied their histories may be, watch companies exist to make and sell new watches. If the current lineup stops selling, then the companies simply stop “being”. As such, Omega, Rolex, Longines, Patek Philipe, and every other watch company you can think of focuses their marketing strategy and budget on getting their latest releases out the of the display case and onto the wrists of the consuming public. Catering to the needs of the vintage watch market is a much lower priority, and in some cases not a priority at all resulting in an wide spectrum of approaches toward their corporate histories.

Thankfully, Omega is one of the companies that supports their vintage community and pays more than lip service to celebrating its past. They use their past products as a constant inspiration for modern reissues. They have a museum. The hold collector’s events. And they are committed to servicing and supplying parts for vintage watches and providing detailed information when available through archive extracts.

Omega isn’t the only watch company that does these things, and some companies do some of these things better than Omega. But Omega’s commitment to their past and those of us that are interested in their vintage watches is real and has been consistent. One of the key resources they’ve had for some time is the Omega Vintage Watch Database, a searchable online tool that pulls up general information by reference number.The database can be found here.

What does the database do?

You simply enter the reference number of the particular watch you want to learn about, hit enter, and it pulls up a fact sheet containing:

- Product Line (Seamaster, Constellation, etc.)

- Year of Introduction

- A Photo

- Collection (Usually “International Collection” for most older watches)

- Dimensions

- Case

- Caseback Type

- Dial

- Crystal

- Bracelet

- Functions

- Movement Type

- Calibre Number

- Other

- Water Resistance

Not all of the fields are complete for every watch reference, and how that data is filled in can be inconsistent. But the output of the database is a basic fact sheet about a particular reference.

What the database does well

The database does a few things right. First and foremost, the service is free. If you have a reference number to start with, you can learn a few basic facts about a watch very quickly. The photos can be useful to tell you if a watch you’re considering is at least somewhat correct. For example if you enter 168.0005 into the database and you’re looking at a watch with a Seamaster dial, you’ll learn pretty quickly that you’re looking at something that is put-together.

The year is particularly useful when comparing with other known data points. For instance if you have a serial number, you can find any number of serial charts by year online. If you compare the serial number and they associated year to the year given in the database, you should expect a match or close to it. A watch launched in the 1970s that uses a 18 million serial number would be an obvious red flag.

What the database does not-so-well

Sadly, there’s quite a list:

- You need to at least know the reference number for it to work well. Reference numbers are inside the caseback, and not everyone has the tools or willingness to take a watch apart. And that makes things hard if you’re at a garage sale or pawn shop trying to do research on a smartphone.

- It’s tricky to use. Sometimes you have to add an extra zero into the “suffix” of the reference number. Sometimes you don’t. Some browsers work better than others. The database has been down over the years for days or weeks at a time.

- It can be tricky to find. Omega has changed the URL and where it lives on their website a few times too.

- The photos can be poor or missing. They seem to be scans of the same images used in A Journey Through Time. They’re often low resolution and not scaled properly for web viewing.

- There are missing references.

- The data is often vague, incomplete, or shallow. Oftentimes many of the data elements listed above are left blank or not that helpful.

- There are blatant errors. More on that shortly.

So did it get cal. 1040 watches right??

Let’s examine the results when searching the cal. 1040 family, listed by my exact search term. Remember the database requires the extra zero. For fun we’ll grade them like a school quiz.

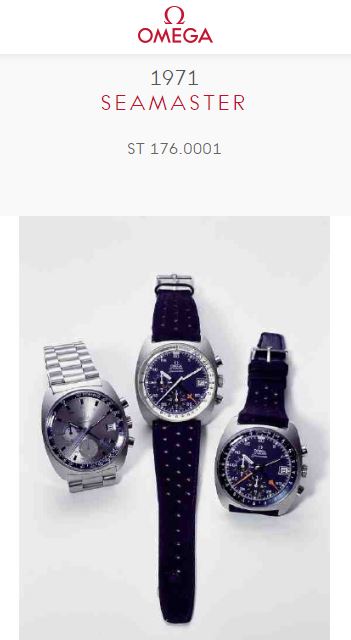

176.0001

Right off the bat the weirdness starts. There’s a photo of three watches, none of them are 176.001s. They are all 176.007s, the same trio photographed and misidentified in A Journey Through Time.

Then the dial is described as “inside “0-60″ tachymeter scale”. As a reminder, the 001’s distinguishing trait is the absence of a timing scale or bezel. The crystal is described as sapphire (it’s hesalite).

Grade: F. It’s obvious the database was populated at a time when the 176.001 was completely misunderstood.

176.0002

This page also starts strangely. The page says “Speedmaster Mark III” but the photo shows a Seamaster dial. This watch is shown in AJTT also, and I question whether Omega actually made 176.002s with Seamaster dials. Even of they did, this photo is a poor choice for the database photo for this reference. My theory is the person assigned to populate the online database was just grabbing pics from AJTT and wasn’t very familiar with these watches.

Grade: C+. Everything else was mostly correct, but showing a Seamaster for this reference is misleading. They should have gone with a D or E dial.

176.0004

Another poor photo choice. This time they used the Speedmaster Mark III version of the dial. Due to the rarity of this dial and the fact that the overwhelming majority of Big Blues are Seamasters, it makes little sense to use this photo.

Grade: B.

176.0005

They got one right – photo and all! Well, let me clarify – they really didn’t get it “right” as much as they got nothing technically wrong. Now seems like a good time to mention that for all of these watches, the “function” field is left blank and the word “chronograph” is never used.

Grade: B+. Omitting “chronograph” from a technical description of these watches makes it pretty tough to give a grade any higher.

176.0007

No photo, which is disappointing for the most common reference in the family. Beyond that everything is mostly correct, but come on.

Grade: D. This reference is known for a variety of dial options. That isn’t mentioned. I should also point out that the database doesn’t mention the gold-plated versions of references 176.005, 176.007 or 176.010. Yes, these omissions count against them.

176.0009

No photo, and while it isn’t rich in information, it’s not inaccurate.

Grade: D+.

176.0010

No photo. The description only mentions one dial variant, which wanders past simple omission and into “inaccurate” territory.

Grade: D-.

378.0801

No photo, for such a special watch?? No mention of the fact that it is a chronometer, and no mention of the fact that the watch is a commemorative, if not limited, edition.

Grade: F. I’d go lower if I could.

Verdict

As far as the eleven cal. 1040/1041 case references, the database does well on two, so-so on one, awful on five references, and doesn’t mention the three gold-plated models. And even on the ones for which it avoids errors it isn’t exactly a wealth of information. I really can’t recommend spending too much time on it even if you’re a total newbie to vintage Omegas. I appreciate that Omega has made the effort and offers this service for free, but I suppose you get what you pay for.

A final word on this series

When I first got into watch collecting, I never would have dreamed of challenging anything in these three sources, which are frequently cited and considered the ultimate authorities by many. I eventually began to realize these sources contained some factual errors and that I was starting disagree with certain conclusions. That is when my obsession with cal. 1040 watches really began. I understood that I needed to draw my own conclusions based my own research, and that the world of watch collecting still contained giant swaths of uncharted territory. When considering whether or not to buy a vintage watch, that understanding can be both terrifying and thrilling.

Still, I’d be lost without these sources, which as a whole have more strengths than weaknesses. My intent has never been to discredit, but to shed light on alternate points of view.

Photo credits: Images on this post came from the Omega Vintage Database in December 2016

Just wondering if you passed on your findings to Omega and if you received any response?

Not specifically about the database. I’ve reached out to Omega on other topics and haven’t received a response.