This is the second of three posts in a series designed assess the accuracy of the most authoritative and commonly cited sources for collectors when it comes to Omegas of this era. My aim is not to discredit these sources or promote my own conclusions to the detriment of their positions. Rather, I hope to further conversation and offer a differing point of view and back it up with the data and observations shared on my site. See Part I on Chuck Maddox’s site here.

The Omega Bible – Marco Richon’s A Journey Through Time

Around the time I started getting into watches, Omega was experiencing a renaissance. Their turnaround from the depths of the quartz crisis was a slow one. The 80s were a decade devoid of interesting new watches, and the 90s started the slow upward climb under the direction of Jean Claude Biver. Omega’s hot streak in the 2000s was accelerated thanks to the co-axial escapement, designed by George Daniels at just the right time. This positioned Omega as an technological innovator at the moment when the world rediscovered its appetite for mechanical watches, now re-positioned as luxury watches.

Omega wanted to remind the public of its long history of innovation in horology by celebrating its past, so it launched a campaign in 2007 titled “Omegamania”, which was to include high-profile collectors’ events, an expansive auction of watches from every era in the company’s history, and a massive book from the Omega Museum’s curator, Marco Richon.

The events and the auction took place in early 2007, but the publishing of the book was delayed a few months, and the book was re-titled A Journey Through Time. The book begins with a condensed version of Richon’s previous book Omega Saga, which is a more straightforward corporate history, then launches into a photographic product catalog, representing damn near everything Omega made up until that point.

AJTT was an instant classic and a must-have for watch collectors. Page after page, chapter after chapter, it is jammed with photos, advertisements and descriptions of watches from all eras. The technological achievements by Omega and the pieces worn by celebrities and heads of state are noted as well. It immediately became the first place to go when trying evaluate a potential purchase. And because it came straight from Omega’s museum, it carried a finality to it: if it was written in AJTT, it must be true. And who am I to challenge it?

Great, but not Perfect

A Journey Through Time succeeded at conveying Omega’s storied past in a single work and remains essential, but it has some flaws. Understandably for a piece with such a broad scope, the there are certain areas where it feels incomplete. For example, although it devotes a ton of space to the Speedmaster, there was obviously demand from collectors in this area, which explains why so many other Speedmaster books have been written to help answer what goes unmentioned in AJTT.

Clarity can be a problem at times too. As I understand it, the book was originally written in French and later translated to English. The translations in the narrative sections are unnoticeable, but they can confuse things in more technical areas and in the descriptions of specific watches. More on that in a bit.

There are some blatant factual errors in the book, too. Some can easily be explained as typos, but there are a few watches pictured that probably shouldn’t have made the cut. I won’t go as far as to say there are blatant fakes in A Journey Through Time (or the Omega Museum, where many of the watches in the book reside), but there are some bad dials in there – either poor redials or fake parts.

It can be easy to hurl rocks at Omega or the Museum for this, but try to think of it from their standpoint. Richon was the curator of a brand’s 160+ year history: the pocket watches, table clocks, prototypes, ladies lines, quartz, electric, manual, automatic, steel, precious metal, dress, casual, sport – all of it. They do a great job at knowing a lot about nearly all of it, but cannot possibly be expected to know every detail of every aspect of that history.

We also now know that Omega acquires pieces for their museum the same way we collectors do: through online sales or at auction. Many times when purchasing through those outlets, you have only the seller’s description to go by and it can be difficult for even seasoned collectors to spot a redial on a model that’s not in their own area of expertise. Plus, the overall standard that collector’s hold watches to has evolved quite a bit in the past decade. “Restored” condition used to be prized, but now is almost a sacrilege for collectors looking for 100% originality.

So what does it say about Cal. 1040?

The 1040 calibre doesn’t get its own section in AJTT and because the book has sections on chronographs, Seamasters, Speedmasters, and Dive Watches there are a mentions of the 1040 watches sprinkled throughout. 1040 is recognized as the company’s first self-winding chronograph, but only briefly. This is somewhat disappointing for such an important milestone. The text briefly discusses the development of the calibre and there are production figures given (82,200 for cal. 1040 and 2,000 for cal. 1041 – I believe one of those two numbers has to be wrong, more here), but the watches themselves are the main feature. Following are my thoughts on some of the most interesting watches included as well as some watches that are noticeably absent.

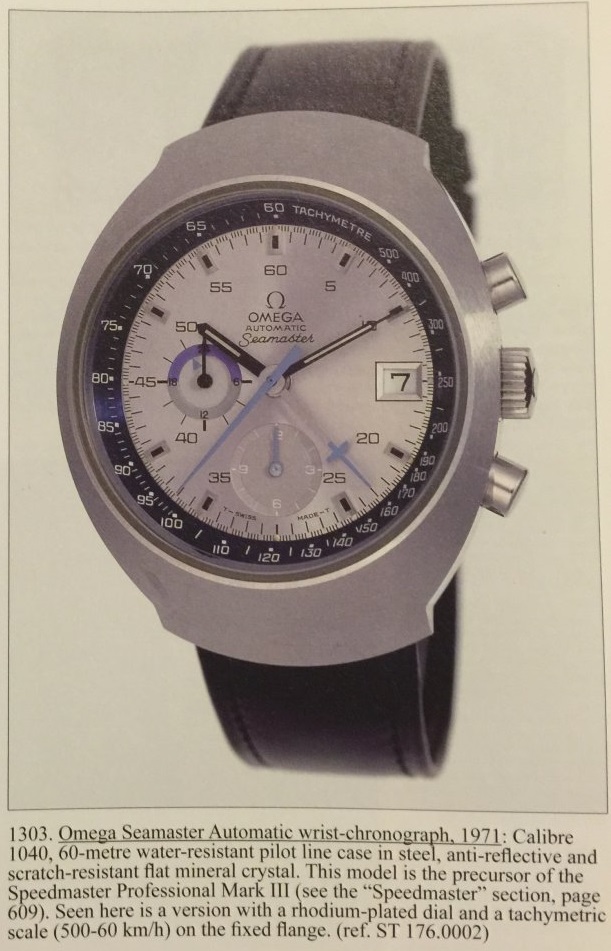

176.002 Seamaster

AJTT features 176.002 with a Seamaster dial (A3 to be exact) on page 551 and refers to it as the “precursor” to the Speedmaster Mark III. Precious little else is mentioned. The watch comes from the museum’s own collection, and given the fact that Omega owns it and Richon decided to include it in AJTT, collectors have taken this has evidence that this specific dial/case combo was a legitimate combination. Some collectors have taken it a step further and used this as proof to justify any unusual or unexpected dial/case combinations on chronographs from this era.

- The caption says this is the precursor to the Mark III, but elsewhere in AJTT the Mark III is referred to as the first automatic chronograph from Omega.

Personally, I’m skeptical. I suspect that reference 176.002 originally was sold only with Speedmaster Mark III dials (dials D or E) and that the example in the collection probably had its dial changed incorrectly during a service. I wrote about how this can and has happened before. In general, I’m more skeptical than most when it comes to cal. 1040 dial and case configurations.

176.007s Mislabeled, and 176.001s not Pictured

Here’s what I wrote in a detailed article on ref. 176.001 back in September:

Ref. 176.001 is never pictured in A Journey Through Time, but it is mentioned once. The caption next to a museum example of ref. 176.007 dating to 1971 ends with the parenthetical “ref. ST 176.0001, which became the ref. 176.0007 ST in 1972”. This caption is unfortunately worded, because the watch pictured has a tachymetre bezel, and is clearly a 007 and not 001. Although purely conjecture, my guess is that this is an early example of 176.007 with the caseback showing a crossed out 176.001 on the inside. The phrase “which became the ref. 176.0007” certainly suggests that 001 preceded 007, but the incorrect identification of the case muddies the waters a bit. There’s a chance that Omega’s records weren’t especially clear and the author just wasn’t too familiar with this particular family of watches, or it was just a poor translation in the text.

I think the fact that either the museum doesn’t have true 176.001 in its collection or Richon simply decided not to feature this watch in AJTT is a big miss. This watch is almost certainly the true first self-winding chronograph produced by Omega, after all.

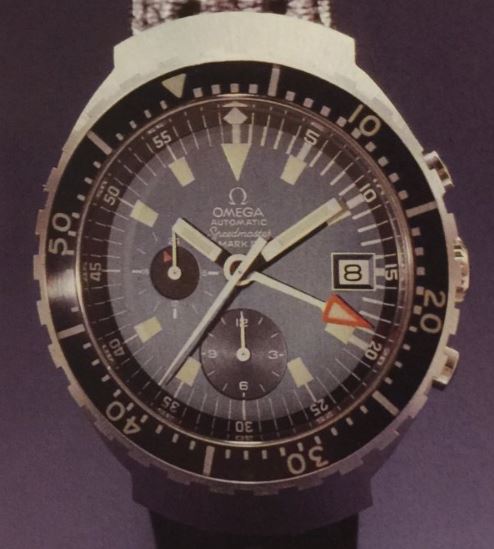

The Speedmaster Mark III Diver

On page 609 of AJTT, Richon features the one and only Speedmaster diver. It looks a lot like the Seamaster “Big Blue” and is in the same case reference, 176.004. So did Omega make the 004 in both Speedmaster and Seamaster variants?

- Could this be a prototype dial? Note the lack of “SWISS MADE” text.

Richon refers to this variant as “very rare”. One thing to note is that the Speedmaster version lacks any “SWISS MADE” text at the bottom. That may mean nothing, but the only other 1040 dials without SWISS MADE anywhere on the dial were prototypes or pre-production dials. My opinion is that Omega did make this dial, but they may not have actually offered it for sale.

Missing Dials

If AJTT included every variant of every watch Omega ever made, it would probably be a 20,000 page book with very small photos. So I get why they didn’t include everything. I consider there to be 31 known dials that Omega made for cal. 1040 or cal. 1041, but only 15 of those are pictured in the book. Of the 15 shown, three are prototypes or very rare. There’s no reason not to include the unusual ones and I’m glad they’re featured, but collectors should be aware that these aren’t examples that they’re likely to come across for sale. Plus, Richon doesn’t mention that two of these dials (the SPAM Mark III dial and the Speedmaster 125 dials that are only featured in Omega marketing materials) are not common.

Despite quite a bit of conflicting information, there is still plenty to learn about cal. 1040 (as well as 1041) in AJTT. You just need to decide for yourself just how credible AJTT and the Omega Museum actually are as sources of absolute truth. We know that the Richon (and the current Museum staff) are just humans and have to make judgement calls. I trust they are doing their best to acquire pieces that are representative of Omegas long history and would never intentionally put something in the collection that they deem to be unoriginal. But they have made mistakes. I’ll admit I’m just some guy so their word carries tons more weight than mine. They are an important and authoritative source, but not 100% perfect either.

As a final note, if you don’t already own a copy of A Journey Through Time, you should try to find one. It isn’t cheap, and it’s not perfect, but it is certainly worth it.

Top image found at omegawatches.com, other https://www.omegawatches.com/news/news-detail/1395/images from A Journey Through Time.

Have really enjoyed the first two parts of this series – looking forward to the 3rd part.

An interesting point made in this instalment was how tastes have changed in the past decade; from “restored” condition being sought-after to “all-original” being desirable. I wonder what drove this change? And will tastes change back?

[Love the whole website. What a resource!]

Thanks for the kind words Ken! A good question- not sure I have a good answer! I just hope everyone that sent their cal. 321 Speedmasters to Bienne kept the original parts!